This is the story of the Indian National Army – the INA, Azad Hind Fauj. Indians today have a wildly unrealistic and highly romanticized notion of the INA. Tragic failures have a romantic appeal, for sure – an attempt to achieve Indian Independence by force of arms, which failed. Contemporary accounts of the INA are either hyper-nationalist in nature and gloss over the actual record of the INA. Objectivity seems to have been abandoned.

The man associated with the INA is Subhash Chandra Bose. Today he is a hero of modern India, and as the Republic ages, the aura around Bose has only increased. The doubts swirling around whether or not he died in the fatal air crash in Taiwan on August 18 1945, and the conspiracy theories around it, continue to titillate and occupy the Indian imagination. The romance of his story is captivating – one determined man, anxious to accelerate India’s Independence, decides to take the military route – and fails. The fact that he tried is a matter of great pride for all Indians.

Many young Indians, when they first hear of the INA, ask why they could not have just fought their way into India with the Japanese Army. After all, there were other Indian army men fighting for the Empire and they could have joined forces with them. The truth is, the INA were not fighting the British Army – they fought the Indian Army. Most of the fighting in Burma between 1941 and 1945 was done by the Indian Army – the sepoy, the rifleman, the tank man and the artillery man. True, they were largely British lead at the start but this changed by 1944. A very vast majority of the Indian Army’s fighting men refused to join hands with the INA.

The INA maintained records like War Diaries that all professional armies do. When the Indian Army was closing in on Rangoon, all the INA papers were destroyed in the retreat. Therefore this account of the INA is pieced together from records of the Indian Army that fought them. A lot of fanciful accounts have been written and much of the military history has been glossed over. It is hoped that this attempt will be seen for what it is – an honest reconstruction from reliable sources.

Regardless of how effective they were in battle, the INA’s existence made an explosive political statement at the end of the War. Churchill had been defeated at the General Elections in 1945 and the Attlee Government just wanted to leave India. The trial of INA officers and the Naval Ratings Mutiny in 1946 – and the public outcry during the INA trials -were important developments to take note of.

However, there was no question of the British suspecting the loyalties of the Indian Army. By the end of 1945, the Indian Army was a thoroughly competent, battle tested, increasingly Indian officered professional fighting force that would perform whatever duty the Government would ask it to do. Most British officers of the Indian Army had genuine affection for their men and the local culture and pride in the professionalism of their men. The behaviour of the Indian Army in battle when confronted with INA forces did not provide any cause for suspecting loyalties. Indeed, Field Marshal Sir William Slim, Commander in Chief of the 14th Army, rated the finest General to come out of the War, writes in his memoirs that in many cases, the ruthlessness of the Indian Army towards their former comrades surprised the British

No, Britain left India because she was too poor, too tired and too much in debt to the United States at the end of the War. It was a hasty departure, a “shameful flight[1]”. It had nothing to do with the Indian Army – or the INA.

Prelude to the INA

The Japanese Government was opposed to the presence of Western powers as colonizers in Asia, and had their own plans of substituting themselves for the British, the French and the Dutch. As you may recall, the British had India and most of SE Asia, the French had Indo-China (Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam) and the Dutch had Indonesia. Historical evidence shows the Japanese interest in Asia was entirely motivated by self-interest – spheres of influence, access to resources, and a protected trading zone very much like the Empire Preference. There was no altruism in their motives – and making a note of this is important as we go further[2].

Japanese intelligence had instructed its operatives to try and make connections with Indian independence activists with a view to destabilizing the British hold over India, well before War began. Major Iwaichi Fujiwara of the Kempeitai was already active in Thailand and Malaya just months before the fighting started, and he did this through an organization called the Hikari Kikan[3]. He would play a key role in the creation of the Indian National Army.

Aggressive Japanese imperialism – on display in the Sino-Japanese War going on since 1932 – alarmed the British. From the mid 1930s the British started taking greater cognizance of a possible Japanese threat to its Asian possessions. Singapore was a British Crown Colony, considered impregnable due to its maritime defences and the presence of the Royal Navy. British Imperial military doctrine depended on the Royal Navy having two Fleets – one in Europe and one in Asia – the Asian one being based in Singapore. The Singapore Fleet would provide protection to the Asian colonies. However the Navy struggled to secure the monies to mount two fleets. There was no expectation that Japanese forces might actually attempt an ambitious landing in Malaya. When France surrendered to the Germans in 1940, the Japanese quickly took possession of French Indo-China. This brought the Imperial Japanese Army, Navy and Airforce within striking distance of Malaya. The independent Thai Kingdom was neutral but leaning towards the Japanese. British military thinking had to take these developments into account. Two Divisions of the Indian Army were rushed to Malaya and told to defend the Malayan coast against a possible Japanese landing. These two Divisions had fresh manpower hastily inducted – but they were poorly trained for the jungles of Malaya.

On December 7 1941, Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbour and declared war on the United Kingdom. The next day, Japanese forces landed in Malaya near Kota Bahru. Facing the Japanese Army were the 9th Indian Division and the 11th Indian Division in addition to British and Australian troops. A series of humiliating defeats at the hands of a superbly trained, well-lead, mobile enemy, followed.

For some months prior to the war breaking out, an expatriate Indian in Malaya, Pritam Singh, had been working closely with Major Fujiwara to set up the apparatus for a Fifth Column. The opportunity came when the Indian Army’s 1/14 Punjab was thoroughly defeated and scattered by the Japanese at Jitra in Malaya in mid-December 1941. Fujiwara and Pritam Singh made contact with one of the unit’s Punjabi officers Captain Mohan Singh. Pritam and Fujiwara explained that Japan planned to convert the POWs into an army that would fight the British for an independent India. Mohan Singh agreed. The soldiers hiding in the plantations after the defeat surrendered to the Japanese. In Jitra, the Indian POWs took over law and order functions in the name of the Japanese. The Japanese advance rolled southwards. The Allies lost almost every battle. There was no air support, and the two old but formidable battleships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales had been sunk by Japanese bombers very early on. The British, Australians and Indians fell back to Singapore.

On February 15 1942, General Sir Arthur Percival, Commander in Chief of the British Forces, surrendered Singapore to General Yamashita of the Imperial Japanese Army at a ceremony in the Ford Factory in Bukit Timah. Nearly 100,000 men, of which 45,000 were Indian soldiers, were taken Prisoners Of War. All the Indian POWs were summoned to a public meeting in Farrer Park. There, Mohan Singh, Pritam Singh and Fujiwara spoke to the POWs and told them Japan would liberate India from the British yoke and asked them to join up. About half of them did. This was the first INA.

Discussions between Mohan Singh (who had by now called himself General Mohan Singh) and the IJA were on going about the state of POWs, the status of the INA, and its role. He was keen to ensure Japanese support, and he wanted a fiery political leader while he would handle all military affairs. He asked the Japanese to get Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose was then in Germany, conducting parlays with the Nazi leadership on using captured Indian POWs to be the advance guard of a German Army that would invade India. He had escaped from house arrest in India in 1941 and made his way to Germany. As a Congress politician, and an associate of Gandhi and Nehru, he carried a lot of credibility as a future political leader.

In the meantime Mohan Singh managed to put together the preliminary military organization of the INA. It consisted of one Division organized into Gandhi, Nehru and Azad Brigades. These brigades were styled Guerilla Brigades. The surrendered arms of the British could equip 17,000 men. An Officer Training School was established. Hospital facilities were set up.

Tensions had been building up between Mohan Singh and the Japanese Army. Mohan Singh was quite insistent that the INA be treated as an equal to the IJA. Senior Indian Army officers who had surrendered were also ambivalent about Mohan Singh’s leadership and his self-awarded title of General. There were valid concerns about the state of Indian POWs who had not volunteered – this was nearly 25,000 of the 45,000 who surrendered.

In mid 1942 Mohan Singh was arrested by the Japanese and interned for the rest of the War. The mutual mistrust of motives was the cause; Mohan Singh thought the Japanese just wanted coolies, and the Japanese did not respect Mohan and his comrades. Most important, a number of Japanese officers who lived by the code of Bushido could not respect men who chose surrender over death. The INA languished.

Bose left Germany by U-Boat and landed in Singapore on July 1 1943. By the time Bose got to Singapore, the tide of the war had turned against the Japanese. The United States was beginning to inflict serious damage on the Imperial Japanese Navy, starting with the Battle of Midway in June 1942. American Marines started to attack and occupy islands in the Pacific, to enable American aircraft to mount bombing raids against the Japanese mainland, breaching the Japanese defensive perimeter in the Pacific.

When he arrived, Bose moved quickly to rejuvenate the INA and repair relations with the Japanese. As a politician of stature, he had the respect of the Japanese. He also appealed to the large Indian diaspora in Singapore, Malaya, Thailand and Rangoon for men and money, and started to admit local Indians into the INA. He set up the Arzi Hukumat e Azad e Hind (Azad Hind Government) in the Andamans – a part of Indian territory in Japanese hands – and took personal command of the Indian National Army.

All that he wanted now was to throw the INA into battle against the British.

The INA Goes Into Action

The Japanese advance through Burma, which began in 1942, slowed down once the Indian Army had completed its withdrawal to the North East frontiers of India by June 1942. The supply lines of the attackers were stretched and there was a pause – it was not so much a pause, as it was a series of engagements punctuated by pauses. From Northern Burma, the Chinese Nationalist Army of Gen Chiang Kai Shek engaged the Japanese without much success. In 1943, the Indian Army attempted an invasion of the Arakan region. The invasion did not succeed.

While the British smarted under this huge military setback, the Japanese were doing their best to consolidate their hold over Burma. Burma was declared a part of the Greater Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. and Burmese nationalist politicians were technically in charge of Burma.

The Commander in Chief for India Lord Wavell realised that it would be foolish to take on the Japanese unless the Indian Army was re-trained for the jungle, taught new tactics and was provided multi-role air cover – to supply the troops, to clear the jungle of the enemy and to get the wounded to hospital. General William Slim was appointed Commander in Chief of the 14th Army, created to consolidate the British response to the defeat by the Japanese.

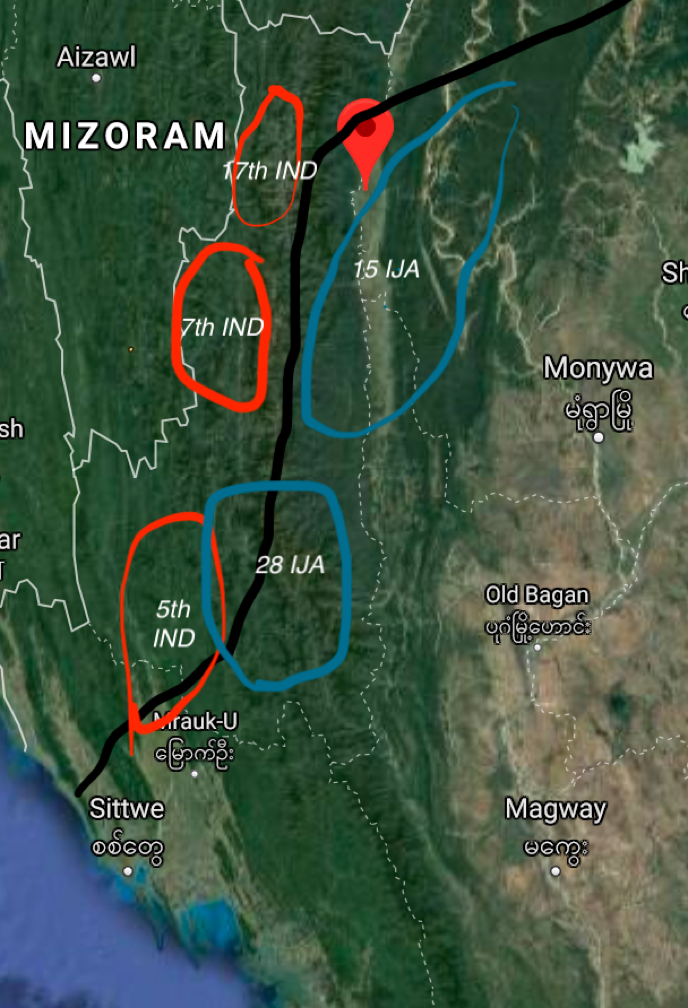

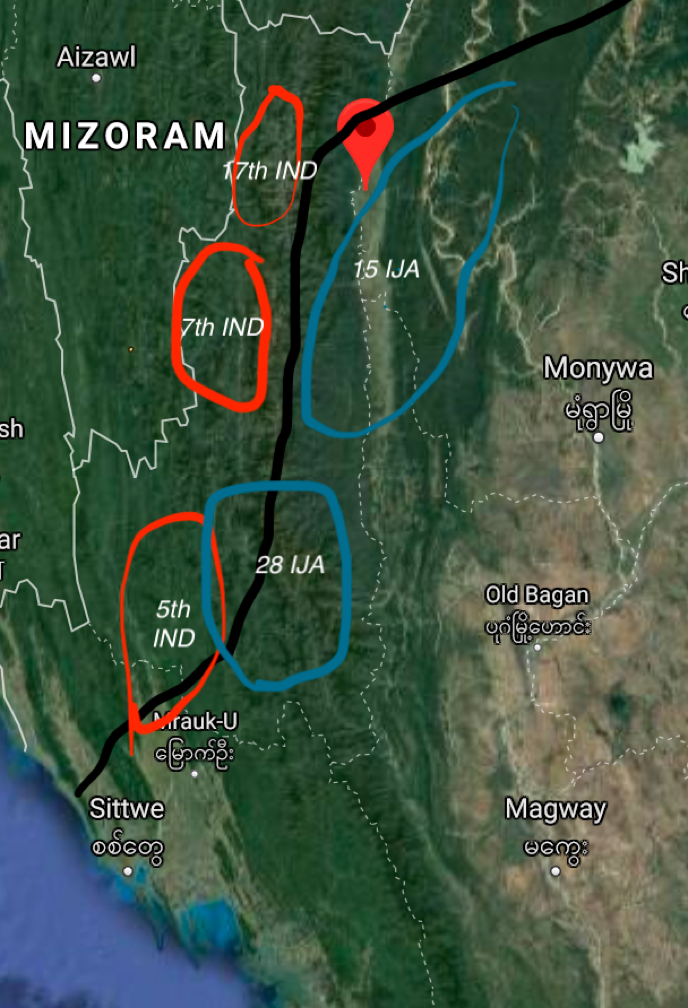

The map below would be useful in understanding how the forces stood in 1944.

The Red Bubbles show the Indian Infantry Divisions and the Blue Bubbles show the Japanese positions.

The War in Burma is a vast subject, but we will only deal with those parts of the War where the INA was involved, with enough battlefield context to ensure the reader is able to form a mental picture. The bibliography will guide the reader to some excellent works on the subject (most notably, Louis Allen’s “Burma: The Longest War”) in case a detailed history of this forgotten war interests him.

The Indian Army was at war with Japan since December 1941. However, it is only in January-February 1944 does the Indian Army report it’s the first encounters with the INA. In early January 1944, reports emerge of INA soldiers asking the Indian armymen to give up, and it appears that in almost every case, the Indian armymen reacted with fury. The derogatory term used by the British for the INA was “JIF” – Japanese Inspired Fifth Column.

In January 1944, Indian Army movements begin anew with renewed focus and fresh Indian divisions – tough, battle-tested ones – in the Arakan (roughly south and east of Bangladesh today). In February 1944 the Japanese managed to trap two Indian Divisions and surround them. (This battle is called the Battle of the Admin Box). To the great surprise of the Japanese, the Indian Divisions withstood the siege and sprung the trap after 28 days. It should have warned the Japanese that the Indian Army may not roll over as easy as they appeared to do in the long retreat, but it did not. Neither did it dismay the Japanese Army a great deal, because their focus was on India.

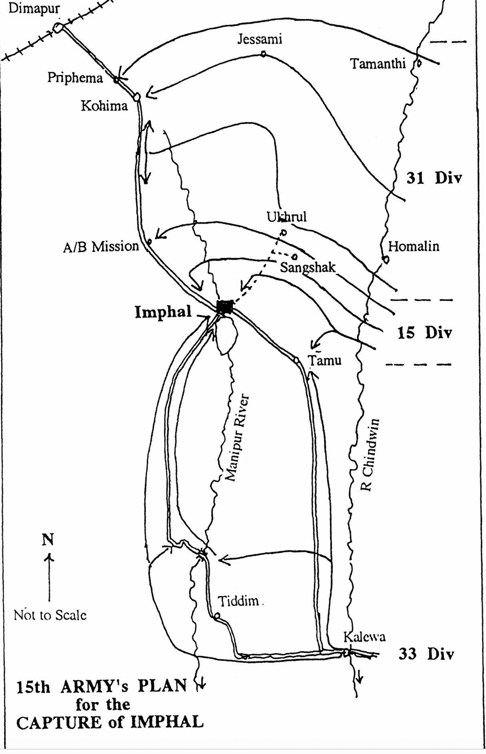

In February 1944, orders were issued to the Japanese Burma Area Command to attack India. The offensive was to be lead by their 15th Army, commanded by General Mutaguchi – a grizzled veteran of Japan’s wars in China. The objective – to capture Imphal and Kohima before the monsoons began (in late April). The Japanese were supremely confident they could pull this off – after all they had chased the Indian Army out of South East Asia and expected no other outcome.

The Japanese attack plan consisted of a thrust from the South towards Imphal along the Tiddim Road in Burma to draw the British to stop the Japanese. This was a feint, and designed to hide the main attack. The main attack would come from another Japanese Corps that would head north and turn west, crossing the hills to burst upon the Indian Army on the road between Imphal and Kohima. They would attack both Imphal and Kohima, cut the road linking Imphal and Kohima, and proceed to Dimapur, reaching the Brahmaputra Valley. As part of the feint, the IJA 15th Army would mount a three-pronged attack from the South.

The INA was delighted with the decision to attack India and assured the Japanese that once the INA was on Indian soil, the people would rise up in arms and overthrow the British. This was a reasonable expectation – the Quit India Movement had inflamed the country, and Bengal was reeling under famine.

The attack began on March 8 1944. It required the Japanese to quickly surround and eliminate the Indian Army south of Imphal, take their supplies, and reach Imphal in two weeks. Gen Bill Slim, however, became aware of the Japanese plan, and instead of rushing southwards, he asked the Indian Divisions to retreat towards the Imphal plain. Fighting retreats are hard to do, but the Indian Army managed to do just that. To do so they had to stand and fight on the road to Imphal and deny the Japanese the advantage of time. The Battle of Tiddim Road was critical to what happened next in Imphal. INA men were assigned the task of supporting Japanese supply lines in the south. They were not happy about this but they agreed to do their part. They were also assigned to assist in the attack on Imphal from the East, from a town called Tamu which is on the Indo-Burma border.

Initial reports of contacts with the INA are not flattering. The INA men would pretend to be Indian Army troops, and gain tactical advantages here and there. This seems to have angered the Indian Armymen. The first surrenders from the INA ranks start as well by March 1944 on the Tiddim Road – in bits and pieces and in one case, a large number of INA Gurkhas. The Japanese attack very quickly got bogged down on the south thanks to some heroic rearguard actions by the 17th and 23rd Indian Divisions.

The Japanese completed a heroic hike across the hills to approach Imphal from the East. The INA was assigned to the Tamu front, and tasked to capture an airfield called Palel on Indian soil. The INA were delighted at the prospect of marching into the motherland. They went into attack, singing songs and shouting “Dilli Chalo!”. However their noisy and gay approach was spotted by a Indian Army Gorkha patrol. Instead of changing sides the Gorkhas practically gunned down the entire section. The airfield was too heavily defended. The INA men made several attempts to take Palel but failed.

The battle for Imphal and Kohima is now part of modern legend. A survey conducted by the National Army Museum in the UK revealed that the British public consider this the most significant battle fought by British forces in their entire history. It was brutal and violent, and no quarter was given nor asked for. The fighting between the Japanese forces on the one side, and the Indians and British on the other, was hand to hand, face to face. Terms like the Tennis Court in Kohima have passed into legend. The fanatical Japanese were indomitable but ultimately, poor decisions made by their commanders on managing supplies for their troops began to tell. In July 1944, the Japanese called off the attack and ordered a general retreat.

It was the largest military defeat the Japanese have ever encountered, handed to them by a composite army of mainly Indian Army men and British forces to a lesser extent. The INA retreat was hard. A particularly grim description of the aftermath of the retreat to Tamu – which was where the INA was based – can be found in the detailed section on the Military History in this blog post.

The Japanese and INA troops were starving, they had no medical facilities and malaria was rife. Men just dropped to the side, dead or too tired to carry on, and were abandoned. If someone happened to die near a river, they were tipped over into it.

The British and Indian Armies – collectively under an umbrella formation known as the 14th Army – went after the Japanese. In August 1944 the Japanese decided to withdraw to the Irrawaddy River and hold the line there. All hopes of going back to India had faded for the INA. The Indian Army coming after the Japanese was just too strong – it was better armed, better lead and they knew how to fight in the jungle.

By now the INA was pretty much on its own, as the Japanese command structure started to crumble. Surrenders continued at a scale that dismayed the INA command. An engagement would take place that would temporarily stop the advance at a particular point. The very next day the men who stopped the advance, would surrender. Apart from wounds and sickness, the new Royal Indian Air Force flying alongside the RAF and USAF were making life very hard for anything military that moved in the day time. The INA had to retreat at night and hide by day.

The British Command waited for their armies to be fully ready before unleashing them in a massive assault in January 1945. The Irrawaddy is a wide and deep river. There is a crossing at a point called Nyuangdu. It was also the widest crossing point, and the British were going to cross here, go straight east through Japanese held lands and capture the town of Meiktila. The INA was at its weakest but the Japanese assigned them to defend Nyaungdu, thinking the British and Indian Armies would not cross there.

Which is exactly what they did. At first the INA managed to hold the crossing for day with their meagre resources. The next day, under a more determined attempt by the Indian Army, the INA folded. Large numbers of INA men surrendered without a fight, and some of their reserves refused to fight.

The Indian Army broke through Japanese lines and dashed for Meiktila, capturing it. The Japanese surrounded Meiktila and there ensued another hard-fought battle. The Japanese siege failed. The INA meanwhile was assigned another defensive position at Mount Popa. Here, the INA performed at its best. It used its lightly armed forces extremely well to hold back a British Brigade. Ultimately a large armoured assault accompanied by severe air bombardment forced the INA to retreat along with the remaining Japanese. Again, large numbers of officers and men just switched to the British. INA officers who defected had no problem signing leaflets that were airdropped on the INA urging them to surrender and offering safe passage.

On April 2 1945, the combined British and Indian Divisions began the race for the 300 miles to Rangoon from Meiktila. The INA, retreating southwards, was repeatedly caught in skirmishes. In two instances the INA men fought with grenades and rifles against a better armed Indian Army, and died to a man. For the most part, INA men chose to locate the Indian Army to surrender. The biggest such surrender took place at a place called Toungoo. The town was of interest to the British Command because it had an airfield. An INA Division was stationed there. When the 255 Indian Tank Brigade approached, the INA men surrendered en masse without a fight.

Towards the end of April the INA leadership left Rangoon, leaving 5000 men to keep the peace. In May the Indian Army entered Rangoon. The last of the INA men surrendered.

The INA originally consisted of POWs from the Malaya campaign. Through Bose’s oratory a large number of Tamils had joined up from the plantations in Malaya. Most these Tamils just took off their uniforms and melted away.

The end was near for the Japanese. Massive air attacks and firebombings made life hard for the Japanese on the home islands. On August 6th and 9th, atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and on August 15th the Japanese Emperor announced their surrender.

The War was over.

Aftermath

The key INA officers – Prem Sahgal, G S Dhillon and Shah Nawaz Khan – were put on trial at Red Fort. The Viceroy, Lord Wavell, wanted a public show. Most INA men who were captured were either dismissed or returned to their former regiments depending on how involved they were in the decision to fight the British[25].

The trial hinged on whether the INA was acting for an independent state or were just a Japanese Fifth Column, waging war on the King Emperor. A stellar defence panel consisting of Sir Bhulabhai Desai, Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sir Dalip Singh, Sir Tek Chand, Asaf Ali, Dr K N Katju, P K Sen and Rai Bahadur Badri Das defended the men in court martial. The panel recognized the enormous political and emotional significance of the trial, conceded the British right to try them, and asserted their right to defend them.

The defence called key witnesses from the defeated government of Japan – Ota Saburo of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Matsumoto Shunichi (former Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs), Sawada Renzo (former Ambassador to Burma), Hachiya Teruo (Japanese Minister to the Free India Provisional Government), and Lt Gen Katakura Tadasu of the Burma Area Army of the Imperial Japanese Army. All of them testified that despite how it may have appeared, the Japanese Government dealt with the Arzi Hukumat e Azad e Hind (Azad Hind Government) as an independent ally. A key witness was Major Iwaichi Fujiwara himself. He was greeted warmly by his old comrades and he testified to his role in fomenting the creation of the INA as a precursor to an independent India.

The trial began in November 1945, and public opinion immediately started to get inflamed. Riots broke out in several cities. Calcutta suffered a general strike. After more than a hundred people died in rioting, Nehru had to appeal to the people to calm down. The Naval Ratings Mutiny that broke out in 1946 invoked the name of Bose and INA.

It was probably unwise of Wavell to try the men in Red Fort – the symbolism with the 1857 Mutiny then could not be denied, inflaming public opinion. Whether it was the defence, or that Indian independence was inevitable and the British wanted to leave on a good note – or a combination of all of them – we will never know. All three INA officers had ordered executions of deserters and informers. The two main charges were waging war on the King Emperor, and Murder. They were acquitted of the former and found guilty of the latter. The authorities conveniently sentenced the three to life imprisonment and then commuted the sentences immediately, setting them free. Further INA trials were planned in 1946. By that time Nehru was well on the way to becoming the head of the interim government, and he warned Wavell not to proceed. The matter ended there.

A Question of Loyalty

Who was the real Indian Army. The 700,000 men who fought as a unit under the British Indian ensign against the Japanese and the INA? Or the 45,000 INA men who fought their former comrades under the tricolor?

Was the Indian Army a mercenary outfit? Indian Army officers will bristle at the suggestion. In fact General K S Thimmayya, who was Chief of Army Staff in the late 1950s, responded to this suggestion. His own brother, Lt Col K P Thimmayya, joined the INA when taken prisoner in Singapore in 1942. They took an oath of loyalty to the Army, nominally in the name of the King-Emperor. But their primary loyalties lay with the fine body called the Indian Army.

Talking about the INA, Gen Thimmayya wrote: “It was difficult for us, therefore, to view this action as anything but patriotic. If we accepted the INA men as patriots, however, then we who served the British must be traitors. This conflict was especially difficult for me because I heard my own brother had gone to the INA.” Among his brother officers ‘the consensus was that we should help the British to defeat the Axis powers and deal with the British afterwards.’

This ethos is best explained by John Masters, who was there one sunny morning in April 1945 on the outskirts of Meiktila, when

“ …Bill Slim personally let slip the final advance…the three divisional commanders watched the leading division crash past the start point. The dust thickened under the trees lining the road until the column was motoring into a thunderous yellow tunnel, first the tanks, infantry all over them, then trucks filled with men, then more tanks, going fast, nose to tail, guns, more trucks, more guns – British, Sikhs, Gurkhas, Madrassis, Pathans…This was the old Indian Army going down to the attack, for the last time in its history, exactly two hundred and fifty years after the Honourable East India Company enlisted its first ten sepoys on the Coromandel Coast.[26]”

The INA was derived from the same ethos, the same organizing principle as the Indian Army. The only difference is that they chose to serve a different master. Had the Japanese organized their invasion of India better and had the INA been better armed, would the outcome have been different?

Most of the Indian Armymen who went to the INA chose to surrender to their former comrades. May be it was familiarity with the old system of regimental loyalties, or a deep familiarity with the officer class. The local recruits (mainly Tamils) just melted away back to the plantations and farms in Burma and Malaya. They felt no loyalty to the INA other than as a transactional, mercenary venture. You will enjoy this anecdote that sheds more light on the complex relationship between the Indian Army and her British officer class. This is when the British and Indian Armies had entered Rangoon, and found only the INA maintaining law and order – the Japanese had all fled.

Sub-Lieutenant Russell Spurr RINVR, a PR officer and his padre friend Pat Magee saw a group of soldiers in Japanese uniforms, then realized they were Indians. A smiling Sikh major approached. “Delightful to see you chaps”, he said, “We couldn’t wait to get this surrender business over.” The men crowded around him and murmured their cheerful approval. But when Spurr explained he could not accept, Magee chipped in: “But we’ll accept a drink.” “By Jove, that’s a jolly good idea”, said the Sikh major, and they returned to the INA mess, where the subalterns crowded round for news. “Pink gin suit you?” inquired the Sikh major. He handed me two glasses. Men who had lately been our enemies snapped to attention as the major called, “Gentlemen. The King–Emperor!”[27]

The maturing of the Indian Army during the Second World War was a critical contribution to nation-building[28]. The army’s officer corps, used to taking orders from British officers and for the most part, not senior enough to have British officers reporting to them, found the situation changed almost completely by the end of the war, as this anecdote shows:

The Nehrus and the Gandhis and the Cripps talked in the high chambers of London and New Delhi; and certainly someone had to. But India stood at last independent, proud and incredibly generous to us, on these final battlefields in the Burmese plain. It was all summed up in the voice of an Indian colonel of artillery. The Indian Army had not been allowed to possess any field artillery from the time of the Mutiny (1857) until just before the Second World War. Now the Indian, bending close to an English colonel over a map, straightened and said with a smile, “O.K., George. Thanks, I’ve got it. We’ll take over all tasks at 1800. What about a beer?”.

The noted scholar Joyce Lebar analysed the political impact of the INA on the Indian Army and concluded:

The INA experience was revolutionary, then, on more than one level. First, as a direct revolution against British rule the INA was partially successful through the British response to the Indian atmosphere surrounding the court martial. Second, as an indirect revolution within the context of the Japanese co-operation the (Indian Army) officer corps was transformed[29].

Did we see an Indian officer corps transformed politically, as Prof Lebar believes? I am unable to agree completely with the second conclusion she draws. I believe the perceptions the British had of the INA changed from contempt to grudging respect largely because of the transformation of the Indian Army itself. The treatment of the INA officers prior to the trial was fair and very respectful, almost as though a hard-fought rugby game had just concluded and the players were exchanging jerseys in the tunnel. I am sure it was not just because of impending independence – it was also because of mutual respect.

The Indian Army’s official history makes very few references to the INA. It is almost as though the Indian Army – the inheritor of the ethos that began on the Coromandel Coast some 300 years ago – has a benevolently ambiguous attitude to the INA which is in keeping with its apolitical nature. Maj Gen Partab Narain wrote in the late 50s that politically the mantle of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose is important in Bengal for vote gathering but he regards lauding the exploits of the INA against the Indian Army to be highly dangerous. Much misinformation, he says, has been published in India since about the INA’s success[30].

The simple INA jawan has to be admired for picking up a rifle and going to war for Independence. Whether he won or lost is irrelevant. He tried – and for that, he deserves our respect.

Remembering the INA

The INA is far from forgotten, as the TV serial seems to allege after the current fashion these days. It is remembered but without any knowledge of their tragic history. There is an INA Museum in Moirang, in Manipur State. There used to be a memorial in Singapore that was demolished in 1945 by Mountbatten, to discourage the South East Asian colonies from developing notions such as independence. Only a plaque stands now at Esplanade Park, erected in 1995 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. The INA’s motto – Unity (Ittehad), Faith (Ittemad), Sacrifice (Qurbani) – was inscribed on the original monument. The words are as relevant to a modern India today as they were then.

More than the romance of the INA, we should feel for those thousands who died in Burma in battle, or of untreated wounds, starvation and sickness. Those who dropped to the road and killed themselves so as not to be a burden. These men died leaving behind a romantic ideal that is cherished by all Indians of all political hues. We need to remember them as those unlucky few who left before their dream of a Free India was indeed realised barely a few years after their passing. They must have died of longing for return, and wondering what was the purpose of their lives – or their deaths.

My choice for an apt epitaph for the INA fallen, would be the words of another Indian, who died in exile in Rangoon longing for his homeland after the first attempt to supplant British rule in India failed in 1858. Here’s the last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar,

कितना है बद-नसीब ‘ज़फ़र’ दफ़्न के लिए, दो गज़ ज़मीन भी न मिली कू-ए-यार में

How wretched is your fate, Zafar! That for your burial, you could not get two meagre yards of earth in your beloved land

Bibliography

Allen, Louis (Major): “Burma: The Longest War” Phoenix, 2000

Bayly, Christopher & Harper, Tim: “Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia 1941-45” Allen Lane 2004

Bisheshwar Prasad (ed): “Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War” 3 Volumes. Combined Inter-Services Historical Section (India & Pakistan) 1958

Brett-James, Anthony (Lt Col): “Ball of Fire: The Fifth Indian Division in the Second World War”, Gale & Polden 1951

Doulton A J F (Lt Col): “The Fighting Cock: History of the 23rd Indian Division”, Naval & Military Press, 2002

Fay, Peter Ward: “The Forgotten Army” University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, USA 1996

Holland, James: “Burma 44: The Battle That Turned Britain’s War in the East”, Bantam Press, 2016

Kirby, Maj Gen Woodburn (ed): “The War Against Japan: History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Military Series Official Campaign History”, Vols II-V. Naval & Military Press 1958

Latimer, Jon: “Burma – The Forgotten War” Thistle Publishing, 2004

Lebra, Joyce Chapman: “The Indian National Army and Japan” (Institute of South East Asian Studies, Singapore, 1971).

Lyall, Ian (Major): “Burma – The Turning Point”, Leo Cooper Ltd, Reprinted 2003

Masters, John: “The Road Past Mandalay”, Cassell Military Paperbacks, 1961 (reissued 2012)

Raghavan, Srinath: “India’s War: The Making of South Asia 1939-45” Penguin 2016

Toye, Hugh: “The Springing Tiger: Study of a Revolution”, Jaico Publishing House, Mumbai, India 1959

A DETAILED MILITARY ACCOUNT OF THE INA

Organizing For Battle

The revitalized INA, after Mohan Singh was ejected, is called INA 2, and it was organized as follows:

Lt-Col Bhonsle – Deputy C-in-C and Chief Of Staff.

Lt Col Shah Nawaz Khan – Planning, Operations, Training and Intelligence

Lt Col N S Bhagat – Administration

Lt Col K P Thimayya – Supplies and Equipment

Lt Col A D Loganadan – Medical Services

Lt Col Jahangir – Education and Propaganda

1st INA Division

1st Guerilla Regiment (Subhash Brigade)

2nd Guerilla Regiment (Gandhi Brigade)

3rd Guerilla Regiment (Azad Brigade)

4th Guerilla Regiment (Nehru Brigade)

2nd INA Division

Formed later, consisting of the Hindustan Field Force

3rd INA Division

Mainly local Indians

Rani Jhansi Regiment

Women volunteers

The INA numbered 40,000 men, armed largely with captured weaponry but no independent armour, artillery or transport.

Dilli Chalo!

Come January 1944, Bose and the INA leadership were based in Rangoon, where its large Indian population welcomed him and donated money generously to the INA (as did the planters in Malaya and the traders in Singapore). The INA was consuming 5 million dollars a month in expenses. Bose was getting restless, as indeed were the officers of the INA.

By late 1942, the Japanese had taken Rangoon, Meiktila and Mytkyna. They did not immediately attack India largely because their supply base was still in Thailand. The military action in 1943 involving the Chindits, the Chinese and aggressive skirmishing between the Indian Army and the Japanese are not directly relevant here.

Bose wanted the INA to be at the forefront of any offensive into India. He believed that the moment the INA came into contact with the Indian Army, the Indian Army would refuse to fight, and that the civilian population of India would rise up in revolt against the British.

In January 1944 the Japanese Burma Area Command tasked the 15th Army to lead the invasion of India. The map above shows positions of the two armies in January 1944. The black line is broadly the front-line. The 17th Indian Division had been in continuous combat against the Japanese from December 1941. It now held positions just south of the road to Imphal. The 5th Indian Division had a distinguished combat record against the Italians and Germans in North Africa, and had been inducted into Burma just a couple of months ago, as had the 7th Indian Division.

In the beginning of 1944, the 5th Indian Division was probing Japanese positions in the Arakan. An offensive in the Arakan – the First Arakan Offensive – had failed. The 7th Indian Division was moving south towards the Japanese. The Allied Command wanted to keep the Japanese on their toes while re-arming and rebuilding.

The first signs that the INA was militarily active came in early January, when the Japanese moved west to occupy a small town called Kalemyo, South-East of Imphal, and there told villagers that a large Indian Army was coming to throw the British out[4]. Very quickly, the 5th ran into the INA. At Nyaunggyaung Wood, during a Japanese attack, the Division reported its first contact with the INA on 17th January 1944.

Here the Japanese gained a footing, and were followed by Sikh Jifs who set fire to the position with a miniature flame-thrower. Just before dawn the Japanese withdrew, after making repeated attacks against ‘D’ Company. The dozen Jifs called out in Punjabi to our Jats to come across and join the Japanese. Their temptations were greeted with indignant bursts of firing. Jifs (Japanese Indian Forces) were Indian soldiers, who, being prisoners of the Japanese, had been forced or cajoled into fighting for their enemy[5].

The term “Jif” was a derogatory term used in the Indian Army for the INA – it stands for Japanese Indian Fifth Column.

The Japanese 28th Army reacted to the movements of the 5th Indian and 7th Indian Divisions quite brilliantly. By early February 1944, they had cut off the 5th Divisions supply routes and infiltrated the 7th’ Indian Defensive lines. The 5th was now pushed towards their administrative area around Maungdaw – also called the Administrative Box. The 28th surrounded the Administrative Box and laid siege to it.

The INA participated in the siege. Some of the accounts of INA involvement are not positive to the INA. On February 8 1944 the Japanese attacked a Military Dressing Station. Lt Col Dr Salindra Mohan Basu, who was in charge of the Station, was taken prisoner after the Japanese shot or bayoneted the living and the wounded. He reports an Indian member of the INA who urged Dr Basu to co-operate and offered safe passage to Rangoon. Dr Basu refused – he was shot and dumped in a ditch and survived by playing dead[6]. The INA may or may not have taken part in the bayoneting of officers and wounded at the Station.

News of the entrapment of the 5th and 7th Indian Divisions was greeted with glee by the INA and other Indians in Rangoon. The Greater Asia newspaper in Rangoon screamed the news from its headlines, and Bose was visited by two members of the 15th Army Staff who assured him that the two Indian Divisions would be destroyed[7].

The Battle of the Admin Box is not so well known as the epic struggle for Imphal and Kohima – it was where the Indian Army stopped losing to the Japanese. General Messervy (CO 7th Indian) and Gen Briggs (CO 5th Indian) lead their men superbly; the Jats, Gurkhas, Dogras, Punjabis and Sikhs in these Divisions fought like tigers and the RAF kept the men supplied by air. On February 28th the Japanese 28th Army called off the siege.

The Japanese 15th Army began its invasion of India. The 33rd IJA Division of the 15th Army would advance from the south on both sides of the 17th’s positions and cutting off the Tiddim road behind the Indians. The 15th IJA Division would advance westwards from the Chin mountains towards Imphal. And the 31st IJA Division would reach a long way west to attack Kohima and cut the road between Imphal and Kohima. The aim was to complete the capture of Imphal and Kohima before the monsoon broke. The map below shows the Japanese plan.

Bose was delighted the Japanese were on the attack, however his insistence that that the INA lead the assault was rejected by the Japanese. The Nehru Brigade under Lt Col Shah Nawaz Khan was to participate and was tasked with participating in the 15th IJA Division’s westward run towards Imphal. He was also tasked with protecting the 33rd’ IJA Divisions supply lines south of Tiddim.

Shah Nawaz did not like these defensive duties – he was disappointed and took his case to other Japanese officers, including Fujiwara, to press for the INA to be given a more active role. Nevertheless, he did as ordered. His Brigade made a heroic effort to get to the small town of Falam which was at an altitude of 6000m. They marched 60 miles with their supplies on their back, and got to Falam first and then to Haka further north. A quarter of the men contracted malaria, but still kept on their feet. Sporadic contacts with the Indian Army resulted. When in Haka, they set a trap for a British officer who was known to be fond of guerilla tactics. They failed to capture him but got twenty five prisoners instead.

Sensing the oncoming Japanese attack on Imphal from the South, the Commander in Chief of the British 14th Army, Gen William Slim, asked the 17th and other formations to withdraw towards Imphal to shorten Indian supply lines (and elongate the Japanese lines by implication). The Japanese attacks began on March 8. The CO 17th Indian Division did his best to organize a fighting retreat, while the fresh 23rd Indian Division was asked to ride south to assist the 17th. The INA accompanied the Japanese on these attacks, on the attack on Tongzhan on the Tiddim Road, and also further up on the Tiddim Road.

Records indicate the INA presence. In one case, the crew of two British tanks on the Tiddim Road saw a Gorkha standing on the road waving a message. When the hatch opened, Japanese soldiers hurled grenades inside the tank[8]. This piece of deception upset the Indian Army no end. On March 14th elements from the Jat Machine Gun Regiment went to assist road-builders who were trapped by the Japanese. In the process they encountered elements of the INA and killed them all, including their Company Commander[9]. Elsewhere, a party of Gorkhas from INA surrendered to 1st Batt/7th Gorkhas. They had been waiting to meet fellow Gorkhas. Amidst many smiles, the INA men gave themselves up[10].

The fighting retreat, now called the Battle of Tiddim Road, of the 17th aided by the 23rd Indian Division helped delay the Japanese on the road from Tiddim to Imphal[11]. It gave Slim the breathing space to airlift the 5th Indian Division to Imphal, and put pressure on supplies of the Japanese. The usual Japanese plan was to fight light but capture British supplies – called Churchill’s Supples – by outflanking the Allies. However British tactics had changed. They chose to fight in a box rather than retreat, and whenever they retreated they chose to burn all supplies. The Japanese supply position was greatly weakened by the delay in taking Tiddim Road. The IJA resumed its advance.

The Battle of Imphal and Kohima

The battles for Imphal and Kohima are now the stuff of military history and legend. It was expected to be an easy victory for the Japanese. Unlike what happened in 1942, this time the Indian Army stood fast. The men were trained for the jungle, better armed, better clothed and supplied. They were encouraged to respond to the traditional Japanese outflanking attacks by going into a “box” and relying on the RAF to supply them. The formations facing them were highly experienced and lead from the front by British and Indian officers. They had good air support.

At the start the INA’s four Guerilla Regiments were directed to Tamu, for the road to Imphal lead directly from Tamu in the east via a small town called Palel which had an airfield.

Here the INA went into battle again. When you cross Tamu, you are in Indian territory. The INA volunteered to mount a raid to seize Palel airport along with the Japanese. The thought of entering Indian territory excited them. A Japanese officer recalled[12]

“the image of the INA troops he had passed on his way to Sibong, wild with enthusiasm as they walked on Indian soil, holding their rifles aloft and yelling “Jai Hind! Chalo Delhi!”.

The detachment was lightly armed and had a blanket each. On the way, still in high spirits, with cigarettes in their mouths, they came across a patrol of Gurkhas (from 4th Batt/10th Gorkha Rifles). The Gorkhas waited until they were close, then opened fire. The INA scattered, and then they made the speech to the Gurkhas to ask them to join them. When the Gorkhas refused, the INA charged the patrol. The Gorkhas returned fire and the detachment had to retire with severe casualties.[13].

The detachment reached the outskirts of Palel. They found the airfield heavily defended and decided to attack at night. There were defensive picquets of the Allies around the airfield. One of the INA officers Capt Sadhu Singh was told to take one of the defenders’ picquets. His small team fixed bayonets and charged. The defenders were Indian troops – they were taken by surprise and quickly put up their hands. When one of the INA officers – who happened to be carrying a Naga spear – lunged at two English officers in the picquet, the defenders opened fire and killed their attackers. The attack was discovered and beaten back.

When dawn came, artillery opened up on the INA positions, killing 250 men. The attack on Palel failed. What is worse, the group that was responsible for the attack surrendered and the rest of the INA detachment retired to Tamu. It was probably the first and last time the INA entered the homeland.

From April to July the INA men embedded in the Japanese 15th Army were in the battlefield but did very little relative to the Japanese. Morale was low all over the 15th Army, not least because the troops were literally starving. The monsoons were heavy and malaria was rife. As the Indian 23rd Division began establishing itself east of Imphal they attacked and drove the INA out of one of the towns they were occupied. In many of these engagements, Indian Army sepoys and riflemen had to be told by their commanders not to shoot INA soldiers but to take them prisoner.

Though the INA never participated in the battles around Imphal and Kohima directly, whatever action they saw on the Tamu Road was brutal. I can find no better description of the horrors they went through than what the 23rd Indian Division saw at Tamu, taken from their War Diary, which is normally a dry, factual record:

“The 5th Brigade (23rd Indian Division) .. entered Tamu the next day (August 3). An indescribable scene greeted the victors as they marched into the border town. The streets were deserted. Vehicles and guns littered the squares and courtyards of the quaint little town. The air was heavy with the stench of decomposing bodies. The dead lay everywhere. They sprawled on the streets, lay on the floor in every hut and hamlet, sat at the steering wheels of motionless lorries. Others lay in heaps at the foot of the temple where they had crawled up to die. Then there were the wounded and the sick, with neither medicine nor food, forsaken and uncared, they were too weak to even cry. Some were emaciated beyond belief by starvation so that even a nourishing meal was poison for their withered intestines. More dead than alive, they waited patiently for the mercy of the end. The damp, steamy heat, the slimy mud and the millions of flies completed the picture, so that on August 4, Tamu bore closer resemblance to hell than to any place on this green earth. When next day the Allied troops set fire to every building that had a corpse in it as the quickest method of cleaning up and disinfecting the town, the picture of Dante’s “Inferno” was complete”[14].

As history records, the failure of the Imphal and Kohima assaults was not because the Japanese gave up. Indeed, Slim calls the Japanese fighting man the finest infantry soldier he has ever seen, bar none. The failure of General Mutaguchi to adequately supply his troops, the failure of his Division Commanders to listen to their second line, and most important, the tenacity and bravery shown by the Indian Army, were key to the outcome. Further, the Allied 14th Army had access to air power, and the presence of light tanks made a big difference. All these factors were instrumental in the British and Indian Armies inflicting the largest and most costly military defeat on Japan in their history. When Gen Mutaguchi called off the attack, the Japanese forces had suffered 80,000 dead. Many of them just starved to death.

The defeat gave General Sir William Slim and his Indian Army the chance to avenge the humiliations of the last two years. Once the monsoon ended the 14th Army went on the offensive

The Retreat

The Japanese and the INA fell back first to the Chindwin River. The retreat was marked by surrenders from the INA. In June the 2iC of the 2nd Guerilla Regiment surrendered from the front line, and exhorted his comrades to surrender (by getting leaflets dropped from the air). Officers started to leave. Punjabi Muslim INA started to surrender in such large numbers that they had to be disarmed[15]. The lack of supplies was so acute that a senior INA officer, Major Garwal, appears to have surrendered for one reason alone – hunger.

The retreat was hard – Fujiwara did his Indian friends a favour by giving them a two day head start. Leaving some men with the Japanese, the INA retreated from Tamu to Ahlow, where the Japanese promised boats to help them cross. There were none at Ahlow. With difficulty they managed to procure a couple of boats and they crossed. Once they got to Teraun, they found there was no food and foraging was out of the question – the Japanese had picked the villages clean. Going down on the River Yu towards the plains was impossible in the rain. The men picked up their wounded, starving and weakened, they walked. Soon, Khan asked the men not to carry the sick and wounded – they were just abandoned on the way. Those who could make their way, made it. The others just died.

Fujiwara, who also retreated with the rest of the Japanese, wrote[16]:

“Japanese and INA officers and men, skinny and half-naked, staggered along with the help of canes. Many of us walked on bare feet smeared with mud and blood, and our faces were ashen, swollen with malnutrition and scaly because of skin disease. Along the edge of the jungle on both sides of the road, bodies of fallen soldiers lay in an endless line. Many of them had already decomposed…Sick persons unable to walk but with some strength left, committed suicide lest they be a burden on their fellow soldiers. A number of them, completely drained of energy, were drowned in a muddy river. Bodies of INA soldiers who died near a river were tossed into the water by their comrades according to Hindu rituals. It was painful to watch.”

A fraction of the men made it to INA’s hospitals in Monywa and Maymyo.

Money and material for the INA from the Japanese dried up by September 1944. The Indian population of Rangoon donated generously for medicine, dressings and even uniforms for the men. Bose learnt the true state of affairs in Imphal for the first time. Shah Nawaz Khan also told Bose of the treatment of the INA by the Japanese. In one instance, the Japanese accused ten INA men of spying for the British – they hung them on trees by their hands, bayoneted them and left them to bleed to death.

November 1944. As the British and Indian Armies swept down from the Arakan and the Chindwin Valley in pursuit of the retreating Japanese 28th and 15th Armies, the INA found itself tasked with defensive roles. Bose met the Japanese in Tokyo and lobbied hard for the INA to continue to have an offensive role in the Burmese War. By now, Bose had been disabused of any notion that the INA would enter India, and instead he redirected the effort towards ensuring they fought and died honourably. For what, is not clear.

The INA forces were ordered to Pyinmana (near where the capital Naypidaw is today). They went there by hazardous train journeys that could only be undertaken at night – as the Royal Air Force, the United States Air Force and the new Royal Indian Air Force were hitting anything that moved in the Irrawaddy valley in the daytime. The relatively untouched 4th Regiment moved to Myingyan, further north right on the Irrawaddy and was expected to give a better account of itself.

There were other problems with the 4th. Mutiny, for one. The majority of the INA men in this Regiment were local Tamils from Burma and Malaya. The officer corps were from the Punjab. Ethnic differences and language differences meant that very soon the Tamils refused to obey orders. Bose found a new commander (G S Dhillon) and handed over the Regiment to him. Dhillon quickly took charge. The regiment had not worn a uniform for months and had taken to taking cover in the day time to avoid air attacks, and hence not drilling. Dhillon changed all that. Another INA Regiment, the 5th, was moved from Malaya – this unit was completely untested but very well equipped. They lost their heavy weaponry due to their ship transport being torpedoed. With nothing but their personal arms, this formation was handed over to the charismatic Captain Prem Sahgal – the only one in the INA with significant combat experience as a Kings Commissioned Officer.

Both officers trained their men hard, but the scenario had altered completely. No longer were they expected to descend from the jungles of Burma into the Brahmaputra Valley. Now they were expected to defend Burma, perhaps die there. Any surprise that the thought of desertion was always in the minds of these men?[17]

In January 1945, the 5th Regiment was ordered to Nyaungu, astride the Irrawaddy, near where the 7th Indian Division was expected to cross on the road to Rangoon. The 2nd Regiment was ordered to Prome, by whatever motor transport available. The third arm of the INA was at Pyinmina – severely battered and mauled remains of the failed Imphal offensive. The Japanese plan was to hold Burma at the Irrawaddy as a defence perimeter.

The Allied plan was to land at the North and the South West of Mandalay, which was south of Nyaungu on the river. Meanwhile the 7th Indian Division followed by the 255 Indian Tank Brigade and the 17th Indian Division punch through at Nyaungu, and make a dash for Meiktila, well to the east of the Irrawaddy. Taking Meiktila would threaten Japanese supplies and depots. The strategy was exactly the same as what the Japanese had done so successfully in Malaya, cutting through enemy lines to capture key nodes of the enemy’s fighting ability[18]. It is a playbook the Indian Army used in Bangladesh in 1971.

In the early hours of February 14th, Gen Frank Messervy and his 7th Indian Division came through to Nyaungdu, with a British Regiment (7th South Lancashires) in the lead. They had no idea how thinly it was defended, or how poorly equipped their opponents were. The crossing at Nyaungu has been described as “the longest opposed river crossing attempted in any theatre in the Second World War”[19]. At the point selected for the crossing, the river was almost 2000 yards wide. No artillery support was provided to keep the crossing quiet.

As the first boats drifted diagonally across the Irrawaddy (to avoid sandbanks) one of the INA units opened up with machine guns. The unit, lead by Major Hari Ram, capsized several of the boats. The 7th Indian’s South Lancashires took heavy casualties and retreated. A smaller diversionary crossing by the Sikhs of the 1/11th was also stopped, four miles down at Pagan. Before it started again, a boat with a white flag was seen to approach the Sikhs. In it were two INA officers offering surrender. Altogether 160 men of the INA surrendered.

The crossing was attempted again at Nyaungu – this time the 7th Division’s 25 pounders, the tanks of the 255 Indian Tank Brigade and the RIAF laid down covering fire[20]. This time, the South Lancashires succeeded – promptly, Major Hari Ram and a hundred men surrendered. Dhillon looked for his reserves and they were reluctant to fight, and implored Dhillon to let them surrender. Dhillon let his reserves leave if they wished, and ordered the rest to Mount Popa. Only 400 men were with him from an original strength of 2000.

Coming along just behind the 7th was the 17th Indian Division, bent on extracting revenge for the disasters they suffered from December 1941 to January 1944. It was a very different 17th though, with Sherman tanks, well-trained fresh men to replace those lost in battle and highly experienced Sikhs, Gurkhas, Dogras and Pathans as the core. Within days the 17th took Meiktila. It so happened that Bose was heading towards Meiktila, tommy gun in hand, wanting to be with his troops, and the 17th was not aware that they were just 20 miles behind him. Bose was dissuaded by Shah Nawaz Khan turned and went to Rangoon[21]. The plan for the 7th and the 17th was just the same – get to Meiktila and turn south to Rangoon to get there before the monsoons.

The 2nd INA Brigade was ordered to Mount Popa and told to hold it. Though not on the route to Meiktila, the position had the ability to harass the Allies. Once again, at Mount Popa, five senior INA officers defected, and arranged for a leaflet drop signed by one of the officers asking the men to defect as well. This enraged Bose but there was very little he could do.

The Japanese now tried to throttle the 17th by surrounding them, and thus began yet another of those epic engagements that is legend in the Indian Army.

The Japanese were trying to re-take Nyaungdu to seal any exit for the 17th Indians at Meiktila. At Mount Popa, Dhillon had first to go and round up those who fled – he succeeded partly. Then the INA began aggressive patrolling to give the impression that they were indeed bigger than they were. They had a few successes, and also a disaster at Taungzin[22] – an INA company was surrounded by tanks and armoured cars of the 7th . Fighting with only rifles and bayonets, they were all killed or captured. Attempts were made to play up the psychological significance of Taungzin by the propaganda arm of the INA. Notwithstanding, disaffection was spreading. Five men were executed for trying to desert. In spite of the declining morale, Lt Col Sahgal got the INA to go on the offensive.

On March 28th, the Japanese broke their siege of Meiktila. The Japanese Army had begun to lose its cohesion. The central Burmese plain was now open to the Allies and the race to Rangoon began. The existing Japanese and INA forces now found themselves overwhelmed as a numerically superior enemy surged.

On March 29th the INA Regiment at Mount Popa went on an aggressive patrol on the Kyaukpadaung-Welaung Road that went tangentially to Mount Popa. There they were ambushed by units of the 7th Indian Division. There were casualties in the INA. Sahgal lost his personal papers that showed the plan to attack Pyinbin. Considering that attack compromised, the INA turned towards Legyi in a defensive retreat.

Legyi was on high ground, allowing Sahgal to observe the surroundings with field glasses. There was also a Japanese patrol concealed at a point overlooking the Welaung Road, with whom Sahgal could get and send messages via radio and field telephone. He would observe Indian and British movements, then get the deployed INA elements to ambush, attack or harass. Air raids were common but the INA had learnt to dig in and avoid casualties (even though the mountain terrain was hard to dig in). British infantry advancing would face machine gun fire and they would retire. This happened a few times.

The next day was a shock for Sahgal – three experienced INA men deserted. Sahgal despaired about whether the enemy knew the true position of the INA. Still he held on. Two days later the British mounted a concerted attack with shelling and mortar attacks and managed to break through the INA position. Once again the INA battalion pushed the British back largely because – as Sahgal called it – “poor tactical sense of the British”. The attacks continued – it was a British Brigade that was in action – but the battalion held.

By all accounts the INA had acquitted itself well against a superior foe – but then the battalion’s mortar officer Yasin Khan and other officers and NCOs deserted that night. When Sahgal learnt that his rear echelon had been overwhelmed, he ordered three platoons to attack. All three had deserted. He got other men to clear the rear. But the next day he found that many more officers and men – more than 200 – deserted. He could not trust the remnants to fight. When I read this account I was astonished. This was a formation that could fight and yet at every occasion the INA officers and men chose to desert. All his company commanders were gone, including men like Abdullah Khan and Yasin Khan who were conspicuously brave under fire. They were not cowards who deserted.

On April 8th the Japanese announced a general withdrawal from the area. The INA’s remaining forces began to leave. They only had bullock carts, and could only move at night.

On April 13th Sahgal managed to get his men clear except for one platoon that was trapped on the Legyi-Popaywa road. The Gurkha who commanded that platoon chose to fight to the death than surrender to the Indian Army – the story goes that when asked to surrender he wrote a note saying “Gentlemen, I do not come”. The situation was fluid. Sahgal and his men headed towards Magwe, hiding by day and travelling by night. Near Magwe a Japanese officer told him the Allies were approaching Magwe. The forces split up – Shah Nawaz and the few survivors of the Nehru Brigade towards Prome, and Sahgal towards Natmauk. He split his forces into two so as not to draw attention. Shortly, he lost one of the two forces under one of his ablest commanders – it transpired that the force was trapped by a British tank unit and the battalion died to a man. The remnants wound their way to a river where a a battalion of Gurkhas was sighted. Sahgal sent his battalion commander with a white flag, and surrendered. They could not fight any more.

On April 22, the first tanks of the 7th Cavalry that entered Toungoo overran the Japanese traffic police at the northern outskirts of the town. The 1st INA Division surrendered to the 255 Indian Tank Brigade. They were disarmed by the 5th Indian Division and put to work on repairing the airstrips which made Toungoo of such importance. Rangoon now lay 166 miles away, and Allied fighter aircraft would be able to cover that distance if based on Toungoo.

The rest of the INA disappeared in bits and pieces. Remnants of the 1st Infantry Regiment surrendered at Magwe on April 17th[23]. Shah Nawaz and his men surrendered to the 2nd Battalion/1st Punjab on May 17th. A larger contingent, who had taken refuge in the INA Hospital at Zeyawadi were overrun by the 5th Indians. Many others just shed their uniforms and melted away, especially the plantation Tamils from Malaya. They were never found.

On May 2 the British and Indian armies entered Rangoon. Nearly 5000 men surrendered here – these were the men Bose had asked to stay and maintain law and order in Rangoon. The Japanese had left by then[24].

Bose and his key associates left Rangoon by road, rail and on foot. He managed to disband the Rani of Jhansi Regiment. Most of the women escaped back to their homes in Burma and Malaya. Some ten thousand INA men survived from the original 45000.

On August 6th and August 9th atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On August 15th 1945 the reedy and scratchy voice of Emperor Hirohito could be heard on Tokyo Radio, surrendering the Empire unconditionally to the Allies.

The War was over.

Footnotes

[1] Leader of the Opposition and former Prime Minister Winston Churchill, speaking in Parliament in March 1947, when Clement Attlee (Prime Minister) announced the date for Indian Independence.

[2] Lebra

[3] Ibid.

[4] Grant,

[5] Anthony Brett-James

[6] Holland, Chapter 16

[7] Fay, p 264

[8] Grant

[9] Grant

[10] Grant

[11] One of my relatives, Capt. S Gopalakrishnan, won a Military Cross while serving as Medical Officer for 3rd Bat/5th Royal Gorkha Rifles in the struggle for Tiddim Road in March 1944.

[12] Allen, pp 221.

[13] Fay, p 290; also Toye, p 231

[14] Bisheshwar Prasad Vol II pp 60, quoting from the War Diary of the 23rd Indian Division for August 1944.

[15] Toye, p232

[16] Fay pp233

[17] Fay, pp320.

[18] Kirby Vol IV pp 263

[19] Kirby Vol IV pp 264

[20] Kirby Vol IV pp 265 and Fay pp320

[21] Fay pp 340

[22] Fay pp342

[23] Kirby Vol IV

[24] Latimer.

[25] Lebar, pp 200-219

[26] Masters ,pp 313

[27] Latimer

[28] See Srinath Raghavan

[29] Lebar

[30] Quoted in Latimer.

Very insightful. Did not realise that Indian Army fought against another Indian Army INA.

Appreciate if you could write more about Subhas chandra bose and his role in INA.

He is revered in Japan while not so much in India

LikeLike

Dear Shiva thanks for visiting the blog and leaving a comment!

Bose is much honoured in India today. Every city has a road named after him and every now and then people ask if Gandhiji prevented Bose from fighting for Independence – some of the stuff around Bose is inane. But he is not forgotten. I am not surprised the Japanese rever him. He was a war-time ally and the Japanese remember that – just as they remember Justice Radhabinod Pal, who was a member of the Tokyo War Crimes trial as the Indian representative judge along with the Americans, British and Chinese. He was the lone dissenter in the verdicts that sent people like Hideki Tojo to the gallows. The Yasukuni Shrine has a memorial to him.

It would be very nice to see how Bose is revered – if you can send some examples I would be very grateful.

Iwaichi Fujiwara, who was in the Imperial Japanese Army, was one of the very few IJA officers who found a role in the post-war Self Defence Force, and retired as a Lieutenant General. He wrote a book about his role in creating the INA. Its in Japanese and the English title is “F Kikan: Japanese Army Intelligence Operations in Southeast Asia during World War II.” I would imagine it is a unique Japanese insight into Bose and the INA.

I will summarise the life of Bose for you over email but there is plenty available. If you can get hold of Peter Fay’s book it is a great start.

Thanks!

LikeLike

Beautifully written. The military story of the INA, which you have eloquently described, is completely new to me.

War in every which way, is messy. There is no straightforward story of heroism and valour. There is much of that, but there is also misery, deceit, dishonour and every other human frailty. The INA seems to have exhibited all of them. But your conclusion is right – there is much to commend in the INA, but equally much that is not so honourable. War tends to make things black and white – the victors were the heroes and the vanquished the villains. It is never that way.

I wonder how the political developments between the INA and the Japanese affected the military events. There is always politics behind any war and perhaps that is also a significant angle to what actually happened on the ground.

I didn’t know about the INA museum at Moirang. If I had known about it before my NE trip, I would have gone there. But then, before your post, I knew next to nothing about the INA.

This is scholarly work. Go forward with your larger project.

LikeLike

Thank you Ramesh – and thanks for the honest feedback over a call yesterday. It means a lot that you would take the trouble to do that.

The politics between the INA, the Japanese Burma Area Command (General Kawabe) and the Japanese Government is reasonably well documented by Fujiwara in his memoir. I could only read it second hand through Peter Fay’s book as it is out of print for a long time. The INA, via Bose, always claimed it could do a larger role than it was capable of, and the Area Command was always sceptical. Even in the 1944 invasion of India, the INA’s role had to be negotiated by Bose and Fujiwara with Gen Mutaguchi (Commander IJA 15th Army) and Gen Kawabe. It was always a tense relationship. Once the Tojo Government fell in 1944, it required a hazardous trip by Bose to Tokyo to talk to Koiso Kuniaki to ensure INA had a place in the scheme of things. However, as you can imagine, the INA had lost its reason for existence – was it to defend Japan or to gain India? The latter was out of the question. I am sure the Burma Area Command was also sensitive to this.

What should have been said in my blog – and it is very remiss of me not to mention it – is that at no point did the INA do to the Japanese what Gen Aung San’s Burma Independence Army did to the Japanese. In 1945 the BIA had a big parade in Rangoon with speeches by Kawabe and others, the IJA gave them a bunch of arms and supplies, let them wear Japanese uniforms. and singing the Burmese anthem they marched out of Rangoon. They promptly attacked the Japanese garrison at Pegu. They were quite shameless about it. T

War is a messy business, as you rightly said.

Thanks for leaving a thoughtful comment.

LikeLike

Ravi,

What a well researched article you have written! Congratulations.

It is a pity that Indian historians have not researched this phase of Indian history deeply enough, your blog should inspire many to delve deeper, as also spur the creative sorts to write books, make movies – reach out and educate a much larger audience on Ittehad, Ittemad, Qurbani. There is a kernel of a book here, Ravi – full of romance, tragedy, irony, unrequited desires – go for it!

My Kodava radar immediately picked out the name Lt. Col. P.K.Thimmayya who was amongst the INA leadership in charge of supplies and equipment. I was further intrigued to discover that he was the elder brother of Gen. K.S.Thimmayya, who was then a Brigadier in the Indian Army. I understand Brig. Thimmayya played a great role in the final settlement of the POWs in Singapore – the War memorial on Sentosa Island in Singapore has a panel on his work. Would the two brothers have come face to face then? What irony that would have evoked – scope for another movie?

Thank you very much for an interesting and enlightening piece!

LikeLike

Thanks Hemanth! Grateful that you could visit and leave a comment. Us writers and hacks live for a pat on the back, a word of appreciation. That alone sustains us in the unheated garrets that we inhabit, smoking too much and drinking too much of cheap plonk!!

Re Timmy Thimmayya, (Gen K S Thimmayya) this is what Timmy himself said about his brother joining the INA: “It was difficult for us, therefore, to view this action as anything but patriotic. If we accepted the INA men as patriots, however, then we who served the British must be traitors. This conflict was especially difficult for me because I heard my own brother had gone to the INA.” I doubt if they encountered each other in the War. But Timmy’s choice was very clear. Among his brother officers ‘the consensus was that we should help the British to defeat the Axis powers and deal with the British afterwards.’

Both these are from Harold Evans’ “Thimmayya of India”. I found them in Latimer (referenced in the biblio).

Thanks Hemanth!

LikeLike

This is passionate and painstaking research. Doing the hard yards and presenting an account that is very informative and educative. A friend (an academic) with whom I shared this essay specifically said that the bibliography is a superb compilation and that some of the references there are not only very difficult to lay one’s hands on but also expensive if one has to acquire them. That is why I began by saying – passionate and painstaking research. Perhaps the fulfilment for Ravi lies in that effort itself. May I suggest that a quick edit/ proof check will help remove some typos / incomplete sentences and avoid the use of (for example) ‘after all’ twice within two sentences. Not nitpicking but visualising that these kind of improvements will help if this paper is sent to any journal for publication.

LikeLike

Thanks Giri. I wanted to get the facts right and hence I searched far and wide. If you determined, you can find what you want I really wish I was back in London for something like this – the National Army Museum, the School of Oriental and African Studies and the British Library are rich in resources and are very helpful. Thank you for recognising the passion behind all this. It means a lot. I could have done a better job with the style of writing. I am learning as I write and I will do the edits we discussed. Indeed I made quite a few changes with your comments in mind. Thanks!

LikeLike

Heartiest congratulations Ravi on such a well researched, scholarly and insightful piece of work. Historical research can be daunting, even for the lovers of history. Your hard work and passion inspires me to dig deep into history.

LikeLike

Thanks Parvesh. Your kind and encouraging words mean a lot. This stuff matters to all of us in India at large. I am so glad it resonated with you.

LikeLike

wonderful scholary work

LikeLike

Thanks Tharak.

LikeLike

Fascinating read . Captures the complexity of the INA and the freedom struggle itself very well . The detailed research and nuanced observations, now par for the course in your posts, make for insightful reading

While a superficial black and white reading of history comes across as evidently incomplete, it is not often that we are able to read about them in more detail, and judge them as being true because of their messy complexities, profound vagueness, inherent contradictions – these to me are markers of approaching closer to the truth of a story

LikeLike